Künstlerhaus Hannover – A Reflection of Architectural Ideology and Bourgeois Cultural Practice

The Künstlerhaus of the City of Hanover—originally built between 1853 and 1856 as the “Museum for Art and Science” according to designs by Conrad Wilhelm Hase—is both a socio-historical and architectural artifact: an ideational structure rendered in stone, a manifesto of early bourgeois self-confidence, and a crystallization point of North German historicism. Located in close proximity to the royal court theatre, it constitutes—spatially and ideologically—a counterpoint to royal representation: an expression of an emancipated bourgeoisie that no longer saw itself as the object of culture, but as its active subject.

Hase’s design for the Künstlerhaus stands paradigmatically for the so-called “Hannover School of Architecture,” whose aesthetic principles draw from Gothic architecture without merely replicating it. Rather, Hase envisioned a “truth in art,” manifest in the constructive honesty, material authenticity, and functional clarity of his architecture. The polychrome façade—composed of subtly shaded bricks achieved through varying firing times—vertical structuring through blind arcades, rhythmic window axes, and sculptural articulation elements follow no decorative caprice but articulate a semantic of usability.

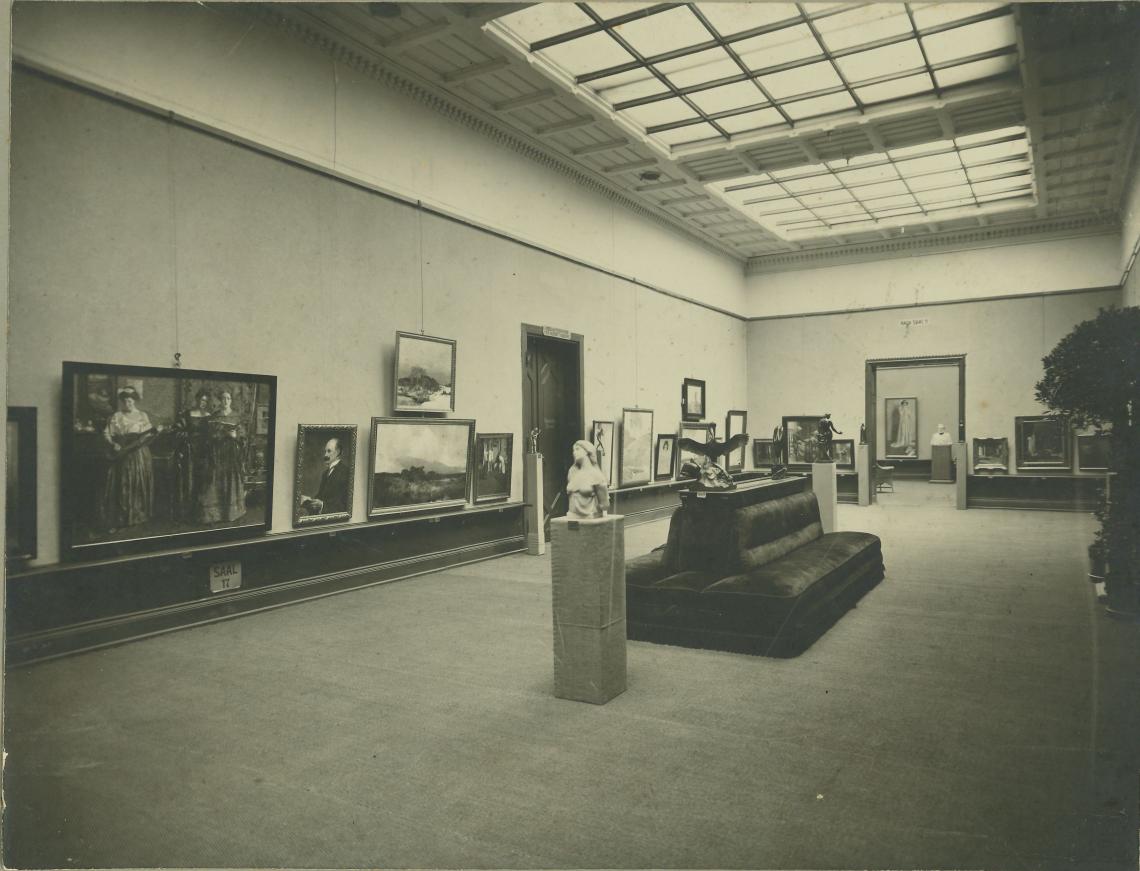

The building was initiated through the cooperation of several bourgeois associations, including the Kunstverein Hannover (established in 1832), and must be regarded as a civil-societal novelty in an era when musealization was typically a state-led endeavor. With its expansive, skylight-illuminated exhibition halls—a light concept that treated daylight as an epistemic medium—the building responded early on to the functional demands of modern exhibition spaces. Its internal spatial sequences, free of classical hierarchical corridors, reflect a usage logic that privileges social exchange and intellectual agility.

Architecturally, the house underwent a series of expansions that may be read as temporal strata: Hase’s own additions in the 1860s and 1870s continued the formal idiom, while the Cumberland Gallery (1883–86), designed by Otto Goetze, introduced a pluralistic vocabulary, amalgamating Gothic, Baroque, and industrial aesthetics. The 1902 renovation by Otto Ruprecht introduced electric lighting and new spatial functions, transforming the museum into a multifunctional cultural venue.

The destruction wrought by World War II and the subsequent rebuilding mark a turning point. Under city planning director Rudolf Hillebrecht, the original wooden roof truss was replaced by a heavy steel structure—a decision questionable both in terms of structural logic and monument aesthetics. The interior was compartmentalized, its former generosity sacrificed to economic spatial division. Only in the 1990s, through the efforts of the architectural office Pax & Hadamczik, did the building regain aspects of its former dignity: light courts were reopened, corridors removed, and spatial generosity restored.

Today, the Künstlerhaus is a hybrid site situated between historical representation, contemporary art production, and urban public life. It is home not only to the Kunstverein Hannover but also to the communal cinema, the Literature House of Hannover, and the Stiftung Niedersachsen. As a listed monument under §3(2) of the Lower Saxony Monument Protection Act, it preserves not merely a building, but a civic space of cultural possibility.

To this day, the Künstlerhaus represents a bourgeois, community-driven conception of culture and a democratic appropriation of space. Architecturally, it is a key work in Hase’s early oeuvre and a canonical testament to North German Neo-Gothic. Its layered history of renovations renders it a document of changing spatial programs and architectural paradigms—from the Gründerzeit through post-war modernism to contemporary heritage conservation.

Künstlerhaus Hannover, Hannover, 2025 - part2

Kunstverein Hannover – fostering critical engagement of and through art since 1832

Founded in 1832 by engaged citizens, the Kunstverein Hannover e.V. is one of the oldest institutions for contemporary art in the German-speaking world. Since its inception, it has pursued the goal not only of exhibiting art, but of negotiating it as a social, aesthetic, and cultural space of experience together with artists and visitors. The Kunstverein serves as an independent platform for current artistic practice—locally rooted, firmly established, and internationally oriented.

An active network of around 1,500 members, a dedicated honorary board of directors and advisory board, as well as numerous supporters sustain the work of the institution. This community is not merely a sponsor of the Kunstverein but constitutes its very foundation.

Situated in the historic Künstlerhaus in the center of Hannover, the Kunstverein develops its program through exhibitions, events, publications, and educational projects. Exhibitions are realized in close collaboration with artists, often as site-specific productions. Approximately four large-scale exhibitions per year—supplemented by the long-standing residency program, discursive formats, and local collaborations—shape the annual program.

Directors of the Kunstverein Hannover have included: Christoph Platz-Gallus (since 2022); Kathleen Rahn (2014–2022); René Zechlin (2008–2014); Stephan Berg (2001–2008); Eckhard Schneider (1990–2000); Katrin Sello (1976–1990); Helmut R. Leppien (1972–1975); Manfred de la Motte (1969–1972); and Rudolf Jüdes (1966–1969).

The Kunstverein Hannover understands exhibitions as engines for institutional development. Since 2022, under the direction of Christoph Platz-Gallus, new formats have been introduced that inscribe questions of inclusion, sustainability, and knowledge transfer into the very structure of the institution. Projects such as the Academy of Life Experience (since 2023), the long-term project Living Archive (since 2023), the initiative Green Kunstverein (since 2025), and institutional accessibility measures developed since The Myth of Normal (2024) reflect art not merely as object or event, but as a membrane connected to diverse social milieus within an ecology of poetic interaction.

An Exhibition for Children (and Other People) (2025), curated by Turner Prize laureate Jeremy Deller, exemplifies this approach: bringing together conceptually driven artistic positions of the past 40 years that employ playful strategies to rethink questions of reception, participation, and education.

Since the exhibition The Myth of Normal (2023), the Kunstverein Hannover has pursued a comprehensive strategy for participation and accessibility, one that takes sensory, linguistic, and social barriers seriously—and actively dismantles them.

A tactile guidance system, developed by artist Peter Schloss, leads visitors through all exhibitions and to haptic QR codes. Audio descriptions and materials in plain language are now integral components of every presentation at the Kunstverein Hannover.

Audience development here is understood literally: Audiences actively develop (the institution) further. Visitor groups and individual visitors continue to shape and evolve the institution’s work. For only that which is truly accessible has the power to resonate.